Sickness is the natural state of Christians

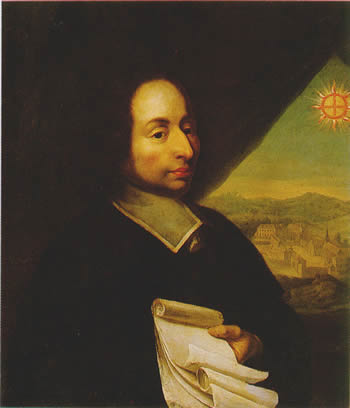

Portrait of Blaise Pascal.

Portrait of Blaise Pascal.

Blaise Pascal, (June 19 1623 – August 19, 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, and religious philosopher. Pascal was in poor health throughout his life. From as early as his eighteenth year, Pascal suffered from a nervous ailment that left him hardly a day without pain. In 1647, a paralytic attack so disabled him that he could not move without crutches. His head ached, his bowels burned, his legs and feet were continually cold, and required wearisome aids to circulate the blood; he wore stockings steeped in brandy to warm his feet.

Partly to get better medical treatment, he moved to Paris with his sister Jacqueline. His health improved, but his nervous system had been permanently damaged. Henceforth, he was subject to deepening hypochondria, which affected his character and his philosophy. He became irritable, subject to fits of proud and imperious anger, and seldom smiled.

Hypochondria, sometimes referred to as health phobia, refers to an excessive pre-occupation or worry about having a serious illness. Often, hypochondria persists even after a physician has evaluated a person and reassured them that their concerns about symptoms do not have an underlying medical basis or, if there is a medical illness, the concerns are far in excess of what is appropriate for the level of disease. Many people suffering from this disorder focus on a particular symptom as the catalyst of their worrying, such as gastro-intestinal problems, palpitations, or muscle fatigue.

In the winter of 1646, Pascal's 58-year-old father broke his hip when he slipped and fell on an icy street of Rouen; given the man's age and the state of medicine in the 17th century, a broken hip could be a very serious condition, perhaps even fatal. Rouen was home to two of the finest doctors in France: Monsieur Doctor Deslandes and Monsieur Doctor de La Bouteillerie. The elder Pascal "would not let anyone other than these men attend him...It was a good choice, for the old man survived and was able to walk again..." But treatment and rehabilitation took three months, during which time La Bouteillerie and Deslandes had become regular visitors.

Both men were followers of Jean Guillebert, proponent of a splinter group from Catholic teaching known as Jansenism. This still fairly small sect was making surprising inroads into the French Catholic community at that time. It rigorously supported teachings of Saint Augustin. Blaise spoke with the doctors frequently, and after their successful treatment of his father, borrowed from them works by Jansenist authors. In this period, Pascal experienced a sort of "first conversion" and began to write on theological subjects in the course of the following year.

Pascal fell away from this initial religious engagement and experienced a few years of what some biographers have called his "worldly period" (1648–54). His father died in 1651 and left his inheritance to Pascal and his sister Jacqueline, for whom Pascal acted as conservator. Jacqueline announced that she would soon become a postulant in the Jansenist convent of Port-Royal. Pascal was deeply affected and very sad, not because of her choice, but because of his chronic poor health; he needed her just as she had needed him.

Suddenly there was war in the Pascal household. Blaise pleaded with Jacqueline not to leave, but she was adamant. He commanded her to stay, but that didn't work, either. At the heart of this was...Blaise's fear of abandonment...if Jacqueline entered Port-Royal, she would have to leave her inheritance behind...[but] nothing would change her mind.

By the end of October in 1651, a truce had been reached between brother and sister. In return for a healthy annual stipend, Jacqueline signed over her part of the inheritance to her brother. Gilberte, his elder sister, had already been given her inheritance in the form of a dowry. In early January, Jacqueline left for Port-Royal. On that day, according to Gilberte concerning her brother, "He retired very sadly to his rooms without seeing Jacqueline, who was waiting in the little parlor..." In early June 1653, after what must have seemed like endless badgering from Jacqueline, Pascal formally signed over the whole of his sister's inheritance to Port-Royal, which, to him, "had begun to smell like a cult." With two thirds of his father's estate now gone, the 29-year-old Pascal was now consigned to genteel poverty.

For a while, Pascal pursued the life of a bachelor. During visits to his sister at Port-Royal in 1654, he displayed contempt for affairs of the world but was not drawn to God.

Religious vision

In October 1654, Pascal is said to have been involved in an accident at the Neuilly-sur-Seine bridge where the horses plunged over the parapet and the carriage nearly followed them. Fortunately, the reins broke and the coach hung halfway over the edge. Pascal and his friends emerged unscathed, but the sensitive philosopher, terrified by the nearness of death, fainted away and remained unconscious for some time.

On 23 November 1654, between 10:30 and 12:30 at night, Pascal had an intense religious vision and immediately recorded the experience in a brief note to himself which began: "Fire. God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of the philosophers and the scholars..." and concluded by quoting Psalm 119:16: "I will not forget thy word. Amen." He seems to have carefully sewn this document into his coat and always transferred it when he changed clothes; a servant discovered it only by chance after his death. This piece is now known as the Memorial. His belief and religious commitment revitalized, Pascal visited the older of two convents at Port-Royal for a two-week retreat in January 1655. For the next four years, he regularly travelled between Port-Royal and Paris. It was at this point immediately after his conversion when he began writing his first major literary work on religion, the Provincial Letters.

When Pascal was back in Paris, his religion was reinforced by the close association to an apparent miracle in the chapel of the Port-Royal nunnery. His 10-year-old niece, Marguerite Périer, was suffering from a painful fistula lacrymalis that exuded noisome pus through her eyes and nose—an affliction the doctors pronounced hopeless. Then, on March 24, 1657, a believer presented to Port-Royal what he and others claimed to be a thorn from the crown that had tortured Christ. The nuns, in solemn ceremony and singing psalms, placed the thorn on their altar. Each in turn kissed the relic, and one of them, seeing Marguerite among the worshipers, took the thorn and with it touched the girl's sore.

That evening, Marguerite expressed surprise that her eye no longer pained her; her mother was astonished to find no sign of the fistula; a physician, summoned, reported that the discharge and swelling had disappeared. He, not the nuns, spread word of what he termed a miraculous cure. Seven other physicians who had had previous knowledge of Marguerite's fistula signed a statement that in their judgment a miracle had taken place. Crowds of believers came to see and kiss the thorn; all of Catholic Paris acclaimed a miracle.

Pascal made himself an armorial emblem of an eye surrounded by a crown of thorns, with the inscription Scio cui credidi—"I know whom I have believed." His beliefs renewed, he set his mind to write his final, unfinished testament, the Pensées ("Thoughts").

Sickness is the natural state of Christians

During this phase of his life, it seems like Pascal lead a ascetic life, abstaining from sensual pleasures, for the purpose of pursuing his spiritual goals. Pascal's ascetic lifestyle derived from a belief that it was natural and necessary for a person to suffer. In 1659, Pascal fell seriously ill. During his last years, he frequently tried to reject the ministrations of his doctors, saying,

"Sickness is the natural state of Christians."

Later in the year 1661, his sister Jacqueline died, which convinced Pascal to cease his polemics on Jansenism. Pascal's last major achievement, returning to his mechanical genius, was inaugurating perhaps the first bus line, moving passengers within Paris in a carriage with many seats.

In 1662, Pascal's illness became more violent, and his emotional condition had severely worsened since his sister's death. Aware that his health was fading quickly, he sought a move to the hospital for incurable diseases, but his doctors declared that he was too unstable to be carried. In Paris on 18 August 1662, Pascal went into convulsions and received extreme unction ( the sacrament of anointing of the sick, especially when administered to the dying). He died the next morning, his last words being "May God never abandon me", and was buried in the cemetery of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, Paris.

An autopsy performed after his death revealed grave problems with his stomach and other organs of his abdomen, along with damage to his brain. Despite the autopsy, the cause of his poor health was never precisely determined, though speculation focuses on tuberculosis, stomach cancer, or a combination of the two. The headaches which afflicted Pascal are generally attributed to his brain lesion.

Pascal's most influential theological work, referred to posthumously as the Pensées ("Thoughts"), was not completed before his death. It was to have been a sustained and coherent examination and defense of the Christian faith. Pascal's Pensées is widely considered to be a masterpiece, and a landmark in French prose.

For after all what is man in nature? A nothing in relation to infinity, all in relation to nothing, a central point between nothing and all and infinitely far from understanding either. The ends of things and their beginnings are impregnably concealed from him in an impenetrable secret. He is equally incapable of seeing the nothingness out of which he was drawn and the infinite in which he is engulfed.

-

Blaise Pascal, Pensées No. 72